February 28, 2011

I is for Information

Social Media and Political Change

Small Changes with Enormous Implications

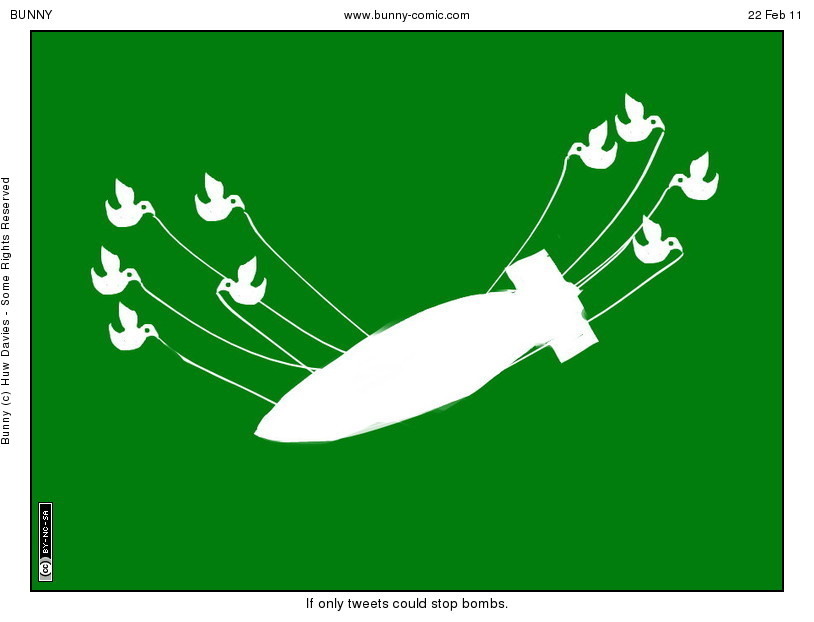

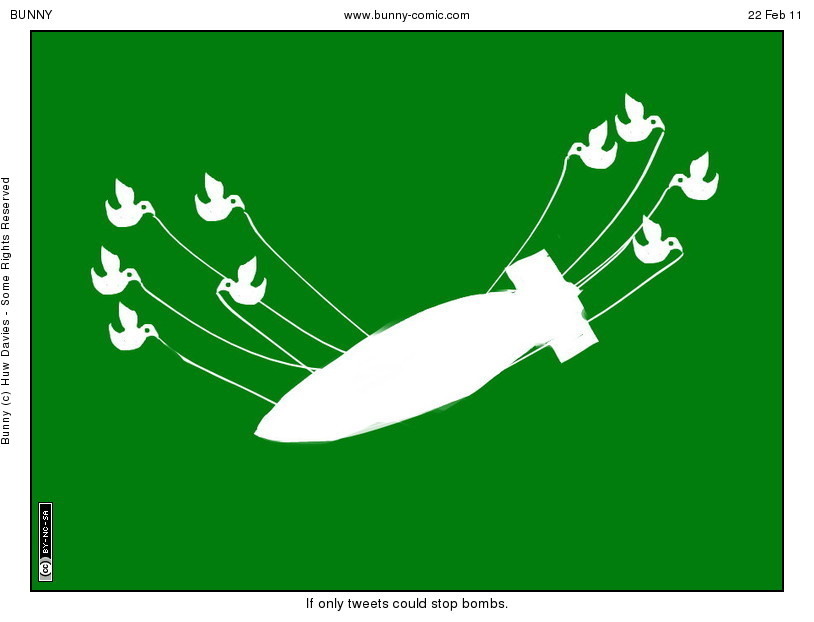

Malcolm Gladwell’s words in 2010 in his “Small Change” article for the New Yorker are almost as if they were written after their time. He writes, “The world, we are told, is in the midst of a revolution. The tools of social media have reinvented social activism. With Facebook and Twitter and the like, the traditional relationship between political authority and popular will has been upended, making it easier for the powerless to collaborate, coordinate, and give voice to their concerns.” Reading this article, one might ask, is social media facilitating any form of credibility for activists? The answer is a fascinating one.

Social media is, of course, giving people who didn’t previously have voices a virtual place to express themselves and a virtual place to collaborate. However, what it is doing in public space is even more impressive. Egyptians have protested their way to a new temporary government and, as such, have inspired others who have been stifled to raise up to demand social, political, and economic changes in places such as Libya. Looking to Egypt, Libyans hope to have similar results from their revolution. What is clear is that information communication technologies are granting the world’s most powerless a greater ability to hold governments more responsible for their injustices by organizing virtually or via SMS text.

Additionally, Kristen Lord proposes greater use of “network diplomacy” between the public and private sectors to improve US public diplomacy. She proposes a balance between the two sectors to effectively utilize the tools Americans have to improve the perception of America in places that might not share economic, social, and political values as Americans do. Privatizing the system some seems a long way off, thought it certainly has its strengths for engaging with sensitive audiences.

February 27, 2011

Just a little... Chaos!

--

A highlight this week: as all those who follow the Public Diplomacy Press and Blog Review already know, Chris Dufour (a.k.a. Du4) was at our Public Diplomacy class today, for an AWESOME discussion on public diplomacy, strategic communication, and strategic coordination, or rather, lack thereof. After all the recent arguments and discussions on the subject of "social media revolutions", the absence of such, and the implications for U.S. foreign policy and public diplomacy, it was refreshing to hear Du4's perspective. I guess I would categorize him as a "cyber realist", who did spell it out in one sentence: "There is no such thing as a 'Twitter Revolution'; there is a revolution that uses Twitter as a tool."

"Find the passion groups in what you're passionate about, and engage with them."

Well, that's inspiring!

Civil Society, Internet Activism… and Betty White

In the Gladwell v. Shirky debate regarding the power of the Internet, specifically facebook and twitter, for social change both authors gave examples of social activism either using the Internet or some other form of communication. All I could think about reading about the power (or lack thereof) of social media tools was the Betty White campaign on facebook for her to host SNL. Clearly this shows my lack of knowledge of world events and my inability to come up with a serious political example for comparison to those of Shirky and Gladwell, but nonetheless it is my only experience with using social media for some orchestrated outcome. I will never forget the day that it was announced that Betty White would indeed host SNL after nearly one million facebook users simply clicked the ‘join’ button for a group dedicated to her hosting. It had deep meaning for me because I had been following Ms. White’s career since her days on the Mary Tyler Moore Show (I had cable at a young age and at a certain time at night nothing good is on but Nick at Nite). It felt slightly empowering, I felt like while I had literally done nothing but click a few links I was a part of something bigger. Three quarters of million people and myself had declared we wanted something and by golly we had gotten it.

I imagine something like this must feel a million fold better for a Moldovan who had joined a facebook group and saw the Communist part in their country ousted. So whether one would call it ‘power’ or not, no one can deny the facilitating factor that facebook, twitter and mobile phones can bring to activism. However I don’t think that the most important issue is how much they help. As Shirky himself states people have been communicating their ideas against dominant powers in many different ways for many centuries, dating back to the days of Martin Luther and his 95 thesis and even way before this. Using whatever tools we have, human beings have communicated their ideas as best we could until a newer way of doing so has made it faster and easier. I am sure Gladwell would agree with this as well; he knows that the sit in movements of the 1960s could not have grown without communication to neighboring cities and states about what was going on in Greensboro through the use of newspapers, word of mouth, etc. If it helps, no matter how big or small, why not use it?

However I do understand why Gladwell stresses the importance of human interaction and emotional ties to the effect and strength of a movement. Even Castells mentions in his “The Mobile Civil Society” that the movements would not have worked if people didn’t recognize the person who a text was coming from when organizing protests. The fact that it came from a friend or a family member legitimatized the message, and did give the person a reason to go out and protest.

So I think my final thought after reading both articles is that the goal of any movement is to reach as many people as possible in order to convey the discontent of the masses, and the more people the stronger the message you are sending. How you get to those numbers is by using communication tools which is what Gladwell calls facebook and twitter. And while they certainly will not make of break a successful movement if the people are motivated enough, something tells me that if facebook was a possibility in the 1960s, four college freshman would have definitely been using it to tell their friends, their acquaintances, the world what they were trying to achieve.

Sources:

Manuel Castells, Mireia Fernandez-Ardevol, Jack Linchuan Qiu, and Araba Sey “The Mobile Civil Society” from Mobile Communication and Society: A Global Perspective (2007); 185-213

Malcolm Gladwell, "Small Change: Why the Revolution Will Not Be Tweeted," The New Yorker,

Clay Shirky, "The Political Power of Social Media: Technology, the Public Sphere, and Social Change," Foreign Affairs, January/February 2011, 28-41.

February 21, 2011

Public diplomacy without credibility

I should, by most units of measure, be a strong supporter of Israel. I grew up in the US, usually considered pro-Israel to a fault, have many Jewish and even a few Israeli friends, and am politically open to new information. But I don’t buy their public diplomacy machine. Why?

The term hasbara means “explanation” but it has come to characterize Israeli public diplomacy as a whole. Its all about information, and lots of it, from videos to press releases and targeted news articles. But a quick google gives more information about the Israeli “propaganda machine” than any of their own diplomatic releases. Again, why? Because “‘the failure of the State of Israel in the realm of Hasbara [explaining] ... especially in everything related to the Israeli–Palestinian conflict, is an established fact’” (Gilboa quoting Schleifer). Even Israeli National News has run a story to that effect.

Sure, the ongoing Palestinian conflict is a lot to overcome, but for a long time Israel’s world image was much better than it is now (PD wiki). The problem seems to stem from how they go about their public diplomacy (at least according to critics): heavy handed, explanation-heavy to the point of propaganda (Huffington Post). And as soon as the word propaganda gets thrown around, your credibility is gone.

My first semester of graduate school, in a class on, yes, propaganda, an Israeli student who did a lot of PR work brought a client, an Israeli PD-type official, to class to speak during an official US PR tour. His prepared speech was fine, informational even. Then he (yes, the PD official) and a Muslim student (yes, just a student) spent the next hour arguing policies and actions. Like, really arguing to the point that no other student could intervene, and we all left. (Quietly, in case we suddenly became targets.) Not his finest hour, I’m sure, but it also seemed to reflect on the Israeli policy as a whole – “deny, deny, deny.” (Huffington Post)

Given the Huffington Post’s how-to list for Israeli “propaganda,” its easy to call its tactics strategic communication: define the debate, have a unified message, anticipate your opponent’s actions. But it is in no way engagement, or even communication, doesn’t build social power, soft power, or any other type of power. As Hayden mentioned in class, (quoting Ben Moore?) establishing credibility is an act of power in and of itself. And that’s soft power that Israel doesn’t have.

Gilboa’s defense of Israel might not be unwarranted, given the tone of the most media outlets, but most of all he points out how important an effective PD campaign is to their foreign policy objectives and world image. Their legitimacy as a state depends on it.

Huffington Post, “How Israel's Propaganda Machine Works,” 9 January 2009.http://www.huffingtonpost.com/james-zogby/how-israels-propaganda-ma_b_156767.html

Etyan Gilboa, “Public Diplomacy: The Missing Component in Israel’s Foreign Policy.”

http://arcdc.org.il/attachments/article/24/gilboa_israel_publicdiplomacy_Oct06.pdf

PD Wiki, Israel, http://publicdiplomacy.wikia.com/wiki/Israel

Israel National News, “Melanie Phillips: Israeli Public Diplomacy is a Joke,” 11 January 2011.

http://www.israelnationalnews.com/News/news.aspx/141668

U.S. Public Diplomacy on the wrong foot

The Two C’s: Culture and Credibility in Unstable Times

Kelton Rhoads, author of “The Cultural Variable in the Influence Equation”, writes about the how the culture maybe given too much attention or as he puts it “culture looms as a causal explanation of human behavior” when there are some universally human responses. He writes,

When approaching a culture, of which one has little knowledge or mutual history, it is of course important to locate or develop cultural expertise. When resources allow, culture should be considered in conjunction with other group-level variables, with human universals, with environmental inducements and constraints (and with individual particulars when possible).

Rhoads’s article is of particular interest because culture, at times, is brushed off as not as significant as other concerns in the international system. However, intercultural communication scholars maintain that what is ignored is that culture is the foundation from which people act. Here, Rhoads argues that as humans “we are both similar to and different from each other.” While this is true, the point of concern here is maintaining a balance between recognizing universally human responses versus recognizing cultural responses. The distinction between the two seems easy superficially, but one could beg to differ that it is more complicated.

Keeping Rhoads’ observations in mind, another compelling article for this week was Steven Corman, Aaron Hess, and Z.S. Justus’ article on US credibility in the global war on terrorism. The authors hold that there are three components to having credibility- trustworthiness, competence, and goodwill. Each one of these dimensions, especially trustworthiness, takes time to establish when they already needed to be in existence yesterday. To become more credible, maybe we need to start with the deep tensions that exist and how to best ameliorate them. To do this, the worlds need lower rank cultural officers to make relationships and establish ties for people of other cultures to understand the US similarities to their culture and that, after all, humans have similarities, regardless of culture. Finally, the point is that human universals, culture, and credibility all must be included in the equation in order to pacify world tensions particularly in places with a great amount of social unrest.

February 20, 2011

The Business of Strategic Communication

Maybe I am being a little self righteous, but the Corman, Hess and Justus piece on Strategic Communication made me feel just a little bit dirty reading it. While the business of selling a product is always at least to some degree manipulation, the business of selling a war (if there should be such a business, but that’s a different blog) seems as though it should be about a little more than that. The policy implications at the end of the paper were what made me cringe the most.

The first recommendation is the only one that seems to recognize that there is no way that some people in the Middle East will love Americans today, tomorrow, or in the next six months. This is good thing, because it shows that they are trying to be less delusion in their communication approach. However, there is also a need to recognize that you can’t force “like” on people and that for some people it may never happen.

The second implication is to involve sympathetic Muslims. I think this will work just about as much as a McDonalds commercial with an African American family and RnB playing in the background works on me (about once a month to be honest). Muslims in the Middle East are going to take with a spoonful of salt anyone speaking on behalf of America, no matter what there skin color or religious beliefs are. They are not going to be OK with our War on Terror just because someone who may or may not share similar religious beliefs from the U.S. says so.

Degrading the opponent is an equally bad idea. Didn’t these authors ever hear two wrongs don’t make a right? This is like telling the kid who is being bullied at school to give it back to the other kid in kind. This just doesn’t work. Instead of focusing on the messages that other people are sending out, the number one priority should be fixing our message. If our message becomes more credible then we don’t have to worry about the other’s message. Trying to destroy their message makes ours even less credible in the short and long term.

The last recommendation is having lower level employees deliver messages instead of higher officials. This just shows a lack of understanding the culture that they propagate earlier in the paper. Many cultures appreciate high-level officials taking responsibility for their words and actions. For instance, when something goes wrong in a Japanese business, it is ALWAYS the CEO who steps down, where as in the U.S. blame is passed down from one official to the next. Before deciding that people who have no real power behind the message should be the ones to give the message, maybe they should research whether or not this would be a good strategy in the Middle East or not. They also suggest using a Middle Eastern celebrity (based on research done somewhere they don’t mention). All I have to say to that is REALLY???

In the end sometimes I think we need to take a step back and stop trying to formulate a message. Stop telling people who we are and what we are and why we are so great. Showing is sometimes the best way to convey a message. Just as our war on terror has already delivered a message to the Middle East that almost seems immutable at this point. I don’t want to seem so pessimistic. I do think that if we are taking big steps in showing a new message with ending the Iraq War, but these things don’t happen over night. We have a lot of explaining to do, and not with words.

Sources:

Steven Corman, Aaron Hess, and Z.S. Justus. “Credibility in the Global War on Terrorism: Strategic Principals and Research Agenda”. Consortium for Strategic Communication. Report #0603. June 9, 2006.

February 17, 2011

What do the Turkish Embassy and jazz have in common? A long history together...

Enjoy!

February 16, 2011

"Internet Freedom" (or, the "Military-Twitter Complex")

--

The U.S. should declare February 15 as its official "Internet Freedom Day": meetings, statements, reports... All in one day and all saying basically the same thing: "Open Internet is good" and "The U.S. should/will do more to promote 'Internet Freedom' technologies as a core part of its 21st Century Foreign Policy." Dealing with these very same subjects in my classes and watching the events in Tunisia, Egypt, and elsewhere unfold live on the Internet, makes me all the more ambivalent about these issues.

"Not only is Beijing using its tight control over the Internet to shield the population from news and information related to government behavior, it is now exporting its censorship technologies to other repressive countries, including Iran, Cuba, and Belarus, Lugar's report stated."

"First, let’s be clear that this was the Egyptian Revolution, not the “Facebook Revolution” or the “Twitter Revolution.” Events of the past few weeks belong wholly to spirit of the Egyptian people, not technology. And although it was built on democratic aspirations, this was not a revolution that drew any inspiration from the United States."

"[The network map] is based on the Twitter activity [of the pro-democracy movement], capturing the freedom of expression and association that is possible in that medium, and which is representative of a new collective consciousness taking form. [...] The map is arranged to place individuals near the individuals they influence, and factions near the factions they influence. The color is based on the language they tweet in -- a choice that itself can be meaningful, and clearly separates different strata of society."

"Google Ideas will combine the models of the State Department’s Policy Planning Staff, a think tank, and a private sector company, with resources to implement. In this sense, Google Ideas will be a think/do tank that strives to bring together diverse perspectives from multiple industries to generate new ideas, approaches and solutions to security, social, economic and political challenges in the world."

"Revolutions are not new, nor are transnational contagion or non-state actors who play a key role in world affairs.

What is new -- and what we saw manifested in Egypt -- is the speed of communication and the technological empowerment of a wider range of actors. An information world will require new policies that combine hard and soft power resources into smart power strategies. That is the larger lesson of the revolution in Egypt."

Funnily enough, just a couple of weeks ago we read the piece, “From hegemony to soft power: Implications of a conceptual change” by Geraldo Zahran and Leonardo Ramos (from Soft Power and US Foreign Policy : Theoretical, Historical and Contemporary Perspectives), where they made a very strong case in critiquing Nye's approach as mostly "an apology" or a justification for U.S. global hegemony. With the above discussion in mind, I cannot help but point out the apparent hegemonic streak in this hype about the "New Media" and "Open Internet".

Firstly, the administration has chosen not to criticize its allies in the region (Bahrain or Yemen, for example), while making sure to emphasize their "concern" about the clampdown by the Iranian authorities. Then, there is the increasingly apparent equation of "Internet Freedom" (which the U.S. claims is a fundamental right, en par with other universal human rights) with U.S. interests, which not only hinders the acceptance of the issue by the governments in question, but also runs the risk of actually discrediting this supposedly "sacrosanct" foundation of the "21st Century Public Diplomacy".

To quote James Harkin:

"For big American internet companies like Google and Twitter, the danger is that their interests come to be too closely defined with those of the American government: that they’re seen to be smuggling in statecraft under the guise of delivering technology. In the conspiracy mills of the Middle East, campaigns for internet freedom are denounced as cover for America’s broader agenda, the stalking horse for a shady new military-Twitter complex."

I will leave you with a tweet from what seems to be a mock tweeter on behalf of @Henry Kissinger [Courtesy of Dr. John Brown]:

"Diplomacy has changed so much. Today our diplomats tweet their messages to the public. In my day, we dropped them from 10,000 feet."

--

P.S. - Just saw this new post by Katie Dowd on DipNote: "Opinion Space 3.0 Launches on State.Gov." Will try to "try out" this "universe of viewpoints and ideas" and share impressions, some time.

February 14, 2011

Culture Quiz…Go: The Perception of American culture in Public Dipolmacy

This week’s Saturday Night Live episode (hosted by Russell Brand) highlighted a couple key ideas about culture and its importance in America and abroad and how American culture is perceived both internally and externally. Within the opening skit, Billy O’Reilly quizzes President Obama on American culture. The implication here is that American culture revolves around old time television shows such as the Andy Griffith Show and other Hollywood icons. Today, Hollywood icons are increasing becoming known as ‘international’ rather than American because these productions have saturated international markets. American Actors premiere their movies in cities around the world, not merely in Los Angeles or New York. In Zaharna’s chapter entitled, “Communication, Culture and Identity in Public Diplomacy”, she offers that spreading American ‘cultural’ products such as movies and television shows actually highlight cultural differences, and generally not in a positive manner, between Americans and the rest of the world. Maybe the problem here is that cultures are always changing, which inherently complicates how others perceive cultures, or maybe the problem is that internationally cultural differences are perceived as being negative in some way. For example, last week the government of Iran banned foreign food shows in an effort to protect its citizens from becoming too westernized. This clearly says something about how powerful the cultural diplomacy of food is but also leads one to question what America’s culture is and the power of its influence around the globe.

Former Cultural Affairs officer and blogger extraordinaire, John Brown postulates that American culture, which contributes to the American identity, is a culture of ideas rather than traditions. In Russia, the educational system is designed to rear children into Russian cultural beings who appreciate high culture. Inherently, Brown and Zaharna illuminate the vital importance culture has in communication of ideas between two publics. Zaharna discusses Edward Hall’s notion of low and high context communication types. Regardless of whether America communicates ideas via low-context and Russia communicates ideas with more high-context (or which ever other country), it is first profoundly important that the American government start actively recognizing culture’s formal existence and its power (even if it consists of ideas, it still is the foundation from which Americans communicate). The hesitation for the government to recognize culture is that American culture is so ambiguous and fluid (because of its diverse population consisting entirely of migrants), whereas other governments manipulate their cultural values to appear more constant. An American recognition of culture internally could ameliorate cultural disparities globally and help government officials learn that public diplomacy is all about how states not only verbally and non-verbally communicate but also how states perceive other states (which again is cultural). This, however, will take time. Greater efforts to properly listen to high context communication around the globe could also help improve the perception of American culture (by employing more bi-cultural individuals) and therefore lead to a more secure American public from non-state actors like Al Qaeda. The American government certainly has some food for thought, which it hopefully will take to heart.

Does Russia Have A Corner on the Culture Market?

Cultural Diplomacy blogger extraordinaire John Brown visited class last week and gave a very informative and interesting talk about his work as a cultural diplomacy attaché in Russia for over 20 years. He talked a great deal about the Russian love for culture and how it permeates every aspect of their lives, including their government and how that reverent tone does not translate into American culture.

John Brown pointed out that the Russians have a cultural affairs office, whereas this is something that Americans would not be comfortable with. But this is not because Americans do not value culture, John Brown said that culture was an area that Americans would never make into a bureaucracy or institutionalize. I believe this is because culture and government would be like religion and government- the two don’t mix in America.

This isn’t because Americans don’t value culture, I believe it’s a deep reverence that keeps us away from making a cultural affairs office. Government is seen as stuffy, bureaucratic and in most cases a stifling of creativity, which is the very essence of culture. To Americans, to make culture into something governmental would be to debase culture. John Brown alluded to this a little in his talk but I don’t think that he gives Americans enough credit.

While the average American may not know five American opera singers, most of us know a Robert Frost poem or two. When someone says that they have taken the path less traveled, this means something to us and it has become a part of our everyday language and a common metaphor. We value movies, good movies through various award shows from the Sundance Film Festival all the way to the Oscars. We take pride in artistic achievement in the form of hundreds of art museums and galleries (The Philadelphia Museum of Art being my favorite, and I even have a favorite room).

I understand the point that Mr. Brown was trying to make. Indeed more Americans can and should take pride in American culture, but to imply that it does not mean a great deal to those of us who do appreciate it is a huge disservice. Even those who do not care a great deal about culture knows something of American culture as it taught to us a children in school. We all must memorize a poem or two in school and almost everyone has music and art classes.

So while we can learn a lot from the Russian model of culture in every aspect of life, Americans can also take pride in the deep and vast culture of America which is looked to by other countries (including Russia as John Brown noted) for its cultural additions to our world.

N.B. I am only playing devil’s advocate; I am sure John Brown knows the great culture of America and appreciates it. I am just highlighting it in my blog as a service American culture.

On Russian "Kultura", Ballet, PD, & Stereotypes

---

If you haven't heard yet, Russia's renowned Mariinsky Ballet was in town last week, performing Adolphe Adam's "Giselle". Certainly, an occasion not to be missed! We braved the cold and the somehow prohibitively expensive ticket prices to enjoy two hours of "high culture" on Tuesday night... which, I should say, I am very happy about!

This week I also had the great opportunity of hearing PD blogger-extraordinaire and former FSO Dr. John Brown talk about his work as a Cultural Attaché in Eastern Europe and later Russia (he was among the distinguished guests at our PD class this week!). In his talk, he put a special emphasis on the striking differences he saw in the importance of high culture in the region, and the contrasting disregard for it by Americans. If interested, you can watch (and read) his thoughts on the subject from a little more than a year ago: a similar presentation, which he gave at AU's First Cultural Diplomacy Conference (November 2009). Very insightful, and oh so true!

(Before I go any further, I wanted to share the following compilation of Tchaikovsky's greatest works, by the Royal Philharmonic Orchestra)

Louis Clark - Hooked on Tchaikovsky

To sum up some of Dr. Brown's key points:

- "Seeking the meaning of Russia outside of culture is pointless." Culture lies at the core of "Russianness."

- While, as a contrast, Americans define themselves essentially in terms of ideas: democracy, dignity, liberty, etc.

- This also impacts the way these nations see their contribution "to the civilization of mankind": Russia in terms of its high culture, while America in terms of ideals like democracy and free-market economy.

- Certainly, has major repercussions for the way they conceptualize public and, especially, cultural diplomacy. Can sometimes go disastrously wrong.

I will take the liberty to take this "train of thought" a step further and suggest that perhaps the "exclusiveness" of high culture is not perceived as "democratic" enough by Americans, which also helps explain the underlying general disapproval and dislike of initiatives that involve "high culture" in one way or another. Yet, as R.S. Zaharna says, public and cultural diplomacy need an "in-awareness" approach, if they are to have an impact - i.e. they have to resonate with the other culture, appealing to its ideals, values and interests.

According to Dr. Brown, American public diplomacy has largely failed to do that, especially when it comes to cultures such as the Russian or the Chinese, for whom their own "high culture" and great heritage are of paramount significance. Yet, I should say that the Russians (although the Chinese, too) have not learned that very same lesson themselves, in the sense of finding the right "values" to appeal to through their own public diplomacy. And here I will go back to ballet, which I can confidently say, is perhaps one of the few exceptions to this rule.

The tickets to "Giselle" sold out within days almost a month in advance (especially the more affordable ones), the hall was packed, and although I heard much more Russian and Chinese than I normally would on the streets of Washington, I also saw many Americans, quite a few of them with their children! Obviously, the Russian ballet has not lost its charm. However, it is still very limited in its reach, and as much as I dislike saying it, Russia needs to invest in (the production and export of) appealing pop culture, too.

Very select few are generally familiar with the Russian "pop culture" scene outside of Russia itself (and, certainly, the former Soviet/Socialist space), unless of course an artist or a movie make it to international contests, such as the case with t.A.T.u. or the "Night Watch". And although the Russian so-called "estrada", as well as its movies, TV shows, radio programs, etc. have come a long way over the years in terms of "pop quality", they cannot even begin to rival American or European ones, especially internationally.

Funnily enough, Russia Today TV does not provide any programming of this kind at all. The only thing I have come across so far is this "Moscow Out" episode from last April. I thought I'd share it with you here:

Oh well... (Can we go back to the ballet, now, please?!)

This said, I will end by returning to Dr. Brown's reflections. As he described (quite rightly, I believe), throughout the Cold War, the American pop culture was like a "forbidden fruit" for the Russian people (and especially, for the intelligentsia). However, during the 90's, "[...] as the Russians started consuming more and more of this forbidden fruit, they got indigestion." He said he had never seen so many bad American movies in his life, as in the 90's in Russia: they flooded the Russian (and post-Soviet) "cultural space", inevitably creating a negative and fairly misplaced image of America. Meanwhile, the American government was oblivious to this problem.

A Case of Hard- and Soft-Power Mismatch

Despite pumping billions of dollars in strengthening Pakistan's army and shoring up its dwindling economy, the U.S. has so far failed to sell its soft power in Pakistan. Not only that, U.S. public perception of Pakistan has also sunk to a new low. Only 18 per cent saw Pakistan favorably and 76 per cent viewed it negatively, according to a survey by Gallup.

This shows that the peoples of Pakistan and the U.S. are at cross-purposes with their respective governments. However, since the U.S. has embarked on and spends billions of dollars to sell its soft image to the Muslim world, public perception of America in Pakistan is a grim reminder that something is wrong on public diplomacy front.

The drone attacks have killed many high-profile al-Qaeda and Taliban militants, but it has increased anti-U.S. feelings because of the collateral damage that they exact. For every single al-Qaeda/Taliban leader, a number of women and children also get killed in the missile strike fired by the un-maned drone called Predator.

The air raids also go to the heart of the resentment that Pakistanis feel against the United States, seeing them as an assault on the nation’s sovereignty. The New American Foundation, which tracks drone strikes, estimates they have killed a total of 2,189 people from 2004 through January of this year. Of those, 1,754 were militants.

Only 16 per cent of residents of the tribal areas think the strikes accurately target militants, 48 per cent believe they largely kill civilians and another 33 per cent feel they kill both, said a study by the think tank.

Another survey, which was published by the New York Times on February 12, says that 67 per cent of journalists in Pakistan think that drone attacks is an act of terrorism itself instead of an anti-terrorism campaign. Since journalists drive public opinion, their perception of the U.S. and its war-on-terror shapes public perception of the U.S.

No less than 84 per cent of the journalists are of the opinion that the U.S. is "unjustly meddling" in Pakistani politics. Journalists with this perception of the U.S. feed the media, obviously, with kind of narratives that run counter to the Obama Administration policy of winning hearts and minds in the Muslim world.

The perception of Pakistani journalists, 77 percent of whom view the U.S. unfavorably, influence opinion of Muslims in other countries too. Afghanistan and Pakistan, being theater of the war-on-terror, is the epicenter of war-related news. The local Pakistani journalists also feed international media organizations. Thus they disseminate their view to a wider public across the borders of Pakistan.

The survey report says, "Pakistan’s tumultuous news media is the prism through which United States policy is reflected to the people, who have found themselves at the center of America’s struggle against terrorism."

"So far, the picture has not been pretty: the George W. Bush administration demonized the Muslim news media; Muslim journalists returned the favor. But research shows that the Obama administration has the opportunity to take a more sophisticated approach to those who drive public opinion throughout the Islamic world."

Soft power is embedded in hard power, but the latter should not overtake the former. Hearts of the Muslims cannot be won by smashing their heads.

http://tribune.com.pk/story/118126/gallup-survey-us-public-perception-of-pakistan-sinks-further/

http://www.nytimes.com/interactive/2011/02/12/opinion/20110213_pakistaniopart.html

http://www.dawn.com/2011/02/14/drone-strike-wipes-out-mans-family-faith.html

Fight culture with culture: cultural diplomacy to counteract pop culture

“It is an American knack to present high culture not in a stuffy academic way but in a way that is both respectful and down to earth. To quote a favorite saying of Cole Porter's, "Democracy is not a leveling down, but a leveling up."” - Newsweek

As John Brown pointed out in his conversation with our class, as well as in his blog, cultural aspects of diplomacy, primarily from the US to other countries, are not a focus of most current foreign policy programs.

Back in November, he pointed this out in a post aptly titled “"Out" for the U.S., "In" Overseas?” Even during his tour in Russian ten years ago, he had to create many of his own cultural events for the embassy. Even for an audience, as he points out, very open and appreciative of these types of events. But I get regular invites to classical performances at a European embassy, German films at the Goethe Institute, or other cultural film festivals at a local museum, all funded by the respective embassy or cultural organization. All for an American audience that isn’t known for being overly culturally- or world-aware. Granted, DC is a microcosm and is somewhat unique from other US cities, but it certainly shows the difference in thinking between diplomats from the US and abroad.

Maybe foreign policy leaders assume that many countries already watch primarily US films, we don’t need to fund art-house viewings in other countries for people to attend. But as Van Ham points out, the spread of pop culture is hard to control, and the benefits of cultural diplomacy are equally hard to measure.

Van Ham also points out the concerning results of what “America is associated with abroad: “sexual amorality, domination, warmongering, materialism, and violence” (54). Maybe its hard to measure the benefits of cultural diplomacy, but its easy to see how pop culture makes us look to the rest of the world.

As an example, there are some countries as well that produce a lot of their own pop culture content where a little cultural diplomacy might go a long way. An NPR story just featured the “Go-to” American star for any Chinese films, the token white guy with flawless Chinese that fits any part. He said in the interview that while Americans usually aren’t the enemy in Chinese films, they are hapless and arrogant, and they never get the girl. China’s media market produces much of its own content, but a little high culture to counteract pop music and movies couldn’t hurt.

Back in 2008, Newsweek even featured an opinion piece stressing the need for cultural diplomacy that cited the same examples as Brown, like jazz beamed into the Soviet bloc. “The American cultural ideal has always been to recognize art on its merits, regardless of where the artist hails from, and to make the finest fruits of civilization available to all. This ideal has never been fully realized. But that is no reason to abandon it, especially now when the country's ideals in general are in need of refurbishing.”

“Public Diplomacy: "Out" for the U.S., "In" Overseas?” John Brown, 28 November 2011.

http://www.huffingtonpost.com/john-brown/public-diplomacy-out-for_b_788931.html

“China's 'Go-To' Typical American Guy,” NPR, 13 February 2011.

http://www.npr.org/2011/02/13/133494531/chinas-go-to-typical-american-guy?sc=fb&cc=fp

“The Return of Cultural Diplomacy,” Newsweek, 31 December 2008.

February 7, 2011

Soft Power (as a tool for PD) is all the Buzz or is it just Comedic Relief?

"Obama 2.0": Two Years On

--

January ended a week ago: another month over, which also means another Empire episode on Al Jazeera English (yes, I'm a devout follower as you probably noticed by now). This latest episode was shot in Washington, DC, as a panel discussion at GW University - featuring noteworthy speakers: Ralph Nader, Roger Hodge, Stefan Halper, and As'ad Abu Khalil (the "Angry Arab") - and focusing on the evaluation of President Obama's foreign policy performance two years after taking office.

In "Obama 2.0", the discussion focuses on American "soft power" (or rather, the lack thereof) around the world, its sources, weaknesses, and the reasons for its failure. Here is the discussion in full:

(Please note that the program was shot some time mid-January, and was aired on January 24 for the first time - much earlier than Egypt erupted. That is why the references to North African "revolutions" come only in terms of Tunisia. Nonetheless, the conversation does touch upon the volatility of the region and all the hypocrisy perceived by the local Arab publics.)

Yet again, if you don't have the time (for whatever reason) to sit through the entire piece, I would suggest you look through the following segments that were - sort of - the starting points for the discussion. The first one focuses on "The Imperial Presidency":

Interesting, and very relevant to the discussions we have been having in the public diplomacy class this week. The program makes the point that Obama was indeed a great speaker - especially compared to his predecessor - and when it came to rallying the international public, he was certainly much more successful in getting the message across and inspiring hope beyond the American borders.

Yet, two years on, very few of his foreign policy promises actually materialized, resulting not just in the same old disillusionment, but perhaps even in net loss in terms of improving perceptions abroad ( --> the greater the expectations, the greater the perceived dissatisfaction, and thus, much greater disappointment). After all, he can make very eloquent and charismatic speeches, but what people really want to see are actions, and these don't seem to be coming about. Not yet, at least.

Can't help but refer back to my favorite concept that serves (in my opinion) as one of the core foundations of public diplomacy: diplomacy of deed. Instead, this discussion points to "the gap between words and deeds", and how, over time, the U.S. is losing its so-called "soft power". Oh, and certainly: they could not pass on the hypocrisy of selective democracy promotion/enforcement, which has been demonstrating itself only too well over the past several weeks.

Watching this program now could not have been more timely: after a week of reading on soft power, hegemony, and the predominance of American values and structures around the world, such formulations and framing by Al Jazeera seem to make quite a lot of sense. (But hey, let's not forget their own perspective, and their own, so-called agenda. That granted, both, the channel itself, and Marwan Bishara especially, need special recognition for raising these questions in the first place, and more importantly, for making it in a pretty legitimate and "backed-up" way.)

The second segment deals with "Obama's Wars" - the peculiar similarities and differences between Afghanistan and Iraq, American tactics, the losses in terms of "hearts and minds", and the implications for the future of U.S. foreign policy (featuring Jeremy Scahill and Matt Hoh).

Certainly, there is a lot of emphasis on the military spending, as well as the "Counterinsurgency" program, which some on the panel contend, is not just not working, but is fueling further disillusionment and extremism among the locals. Here, it would be appropriate to go back to a term I really like - cultural intelligence, or "CultInt". This term truly captures the conceptual incoherence of the effort, I think: garnering support from the local population by combining "culture" (broadly defined) with "intelligence" (no, it's not referring to competence, but rather, information gathering). In short, studying the "target public" from within so as to be able to use various elements of its culture against itself. And it is also here that one can observe the very thin line where "soft power" easily transforms into "hegemony", if not outright "coercion". (Remember "Avatar", the movie?)

It is difficult not to go into the ethical implications of this effort. But even if that is ignored "for the sake of national security", the issue still begs the question: what is national security? I thought the fact that most of the insecurity comes from negative perceptions of the U.S. among certain parts of the international public was recognized ten years ago. But then it seems to take a little longer for policymakers to fully comprehend that perceptions are also directly related to actions ("public diplomacy of deed", remember?).

(Yes, some may ask why Obama's personal effort is so decisive. But then, being the democratically-elected President and the Commander-in-Chief of the military, he is also the "Persuader-In-Chief", speaking on behalf of all of America.)

With this in mind, it seems like Egypt does indeed present the major public diplomacy challenge for Obama (if not the biggest foreign policy problem). There has been a lot of attention as to what the White House (or anyone else from the administration) will or will not say. And yet, what will matter in the end is what his administration actually does, whether overtly or not (apologies to all the speech writers!).